Modern Womanhood as the Polished Cage of Independence

When I was a child, my dreams were not small: corsets, broad skirts, heavy forest-green gowns dragging across wooden floors. I imagined myself as Anne, but taller, darker, and dressed like a gothic heroine who could still milk a cow at dawn.

My mother, however, was not impressed. She believed in trousers. Not just trousers, but short hair too — as if she were running a boot camp where femininity was contraband. (And here’s the psychological note for the record: stripping women of their hair has always been a method of erasing identity. From Auschwitz to prisons, haircuts were never just hygiene — they were humiliation, a theft of personality. My mother never read those studies, but instinctively she played from the same manual.) So she cut my hair, forced me into jeans, and told me that ribbons were for idiots. Personality was not something I was supposed to develop. I was to be her worker, her little slave, the child who brought home money, not the child who demanded puffed sleeves.

The clothes I wanted — long hair, velvet ribbons, dresses that whispered of other centuries — they would have cost her money. Money she expected me to earn for her, not to spend on myself.

When I was six, I didn’t just collect aluminium cans and rusty metal— I collected salty dreams of velvet gowns and ankle-length skirts, heavy dark green fabric whispering secrets. I imagined corsets that cinched not my waist but the world, puffed sleeves like wings, long hair like Anne of Green Gables drifting behind me. My mother, however, was certain of three things: trousers, practicality, and that my hair should always be cut short. “Your hair is too thin,” she insisted. “You’ll look silly.” So she snipped, and I wore trousers stuffed into socks, I wore tight floral fabric pants I despised. Sometimes, I tied scarves over my head trying to fake the long hair I didn’t have. (Here is something I looked up later: in concentration camps, women had their hair shorn as a weapon of humiliation and erasure of identity. Women’s Lager narratives talks exactly about how the forcible removal of hair was part of the ritual of dehumanization. )

I asked why she kept cutting my hair. She said it was cheap, easy, and I mustn’t look “fancy” — I was meant to bring in money, not attention. So I scavenged metal in the gutters, traded in junk so I could maybe one day afford a dress she would hate.

At about eight, I landed in a children’s home. I thought: maybe here I can breathe. I declared I would not wear trousers from home anymore. I would wear dresses. The caretakers laughed. Dresses? At my age? I was put in baggy tee-shirts, plain pants. The hair remained cropped. By ten, I had silently surrendered. I grabbed the jeans, the dusty pants, the uniform nobody asked me if I wanted. I decided I might as well become invisible—though my bones still ached for puff sleeves and long dark gowns.

read more:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1261195/

https://doaj.org/article/876dd819050d43ae98d5dfdffff2f7aa?utm_source

By the time I was ten, I had already surrendered to the uniform of invisibility. Jeans, t‑shirts, hair cropped like a forgotten scalp in some military camp. My dreams of corsets and green velvet skirts had not yet died, but they had retreated into shadow, like vampires waiting for the moon.

I had grown up without parents who could teach me caution, foresight, or the basic protocols of dealing with men. That naivety was a gift I didn’t ask for, and it came with consequences. By fifteen, I had already learned the first, unforgettable, and appallingly explicit lesson: if a man offers help, your body is no longer your own.

The first one was over forty-five, a stranger with a literary air. He had decided I needed to learn obedience the hard way, and apparently, quoting poetry was the prerequisite for sex. I left that encounter with the knowledge that my clothes, my posture, my hair—everything—were not mine to command. If I wanted assistance, if I wanted a semblance of safety, my body became a currency, and my autonomy a negotiable asset.

So, naturally, I learned to earn my independence with as little visibility as possible. Baggy army pants, copper-toned t-shirts, gender-neutral appearances: practical, unremarkable, unremarkably safe. ADHD only made the oversized cardigans and flowing dresses a trap—one could trip over their own sleeves or a stray object at home, drawing attention in ways I could not afford.

Armed with these lessons, I began to dream again—but not of dresses. Of discipline, of structure, of army boots and routines where my body’s currency could be rationalized as survival. Yet, the faint, stubborn pulse of Green Gables never quite died. Somewhere beneath the trousers and short hair, the corset and puffed sleeves waited, impatient.

(Read more about child soldiers and early encounters with male authority https://fraumutterrenate.blog/2025/09/12/𝙾𝚛𝚙𝚑𝚊𝚗-𝚑𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚝𝚜-𝚊𝚛𝚖𝚢/.)

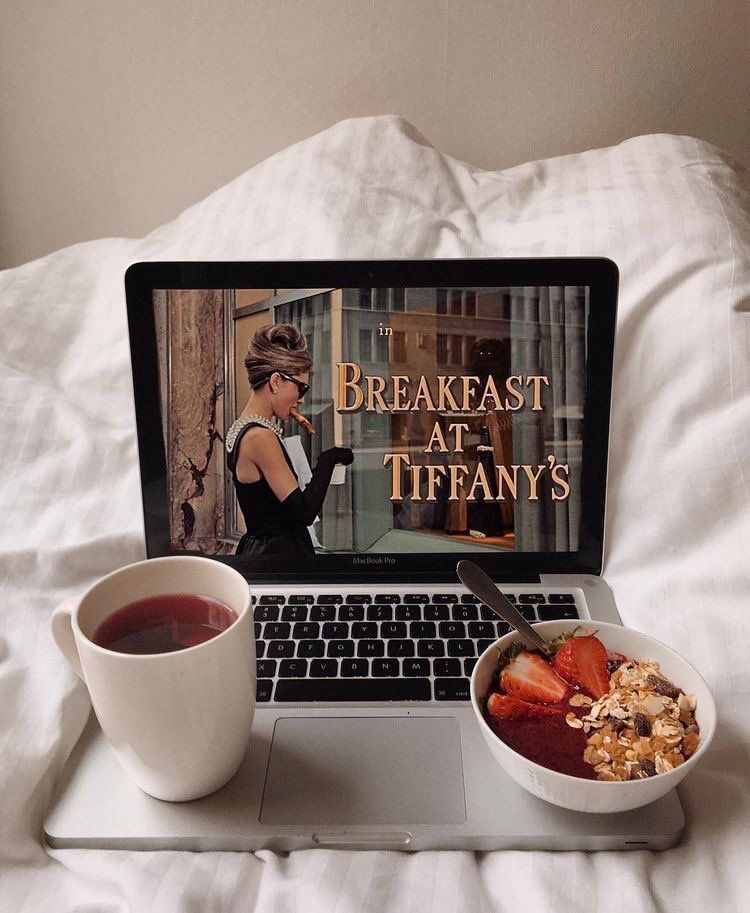

By the time I left the confines of my early life, I had already internalized the rhythm of criticism. Every movement, every choice, every strand of hair was subject to judgment. And yet, in the shadows of my own insecurity, I discovered fascination: women who dared to drape themselves in fabric as though it were armor, Gothic ladies in their black lace, skirts sweeping like obsidian waves. These were warriors in silk and velvet, commanding respect without uttering a word. When I first arrived in Germany, the exposure expanded. Middle Ages reenactment groups with their heavy cloaks, corsets, and chainmail; retro clubs where women dared the 50s silhouettes that I had only dreamed of in the solitude of my room; Muslim women in modest, flowing garments, their presence a quiet, defiant elegance. I realized that clothing was never just clothing: it was a statement, a shield, and, most dangerously, a language men attempted to decode and dominate. Yet, my own sense of style remained trapped in the prison of caution. Every dress I considered was measured against potential male scrutiny: would he leer? Would he judge? Could I move safely in this fabric, in this pattern? The lesson from fifteen remained vivid: safety and autonomy were never guaranteed, and the body had long since become a form of currency. And so, I observed. I absorbed. Gothic, medieval, retro, modest — each style a manifesto of intent, a resistance to the invisible chains society demanded I wear. In their elegance, in their deliberate choice, I glimpsed the map back to myself. It was the beginning of the realization that, even in a world obsessed with “freedom,” women still navigate corridors lined with judgment, where desire and fear collide, and every outfit can be a battlefield. I started studying by myself. Psychology of modesty. History of design. History of wearing. I experimented with style because, well, let’s be honest: everyone who has ever been in Berlin knows you can walk in pajamas and nobody blinks. That freedom, Germany gave me—it was short-lived, but intoxicating. Hours in libraries, bookstores online, learning about why women once covered their hair, why a society can celebrate modesty in one century and despise it in the next. I started noticing the absurdity: a woman wearing a beautiful wardrobe, painting her lips red, and suddenly men start screaming “Oh my gosh, I hate when women wear red lipstick!” Really? That’s the problem? A little advice, darling, just off the side: maybe your hatred will dissipate if you confined your… displeasure… to one woman. Not the entire town. Not the streets, cafes, offices, parks. If you hate red lipstick, maybe wear it yourself, or shut your mouth. Don’t attempt to dictate an entire city’s aesthetic. Simple. Ironically, every time we try to delete men from debates about women’s bodies, female wardrobe, we are forced to put men first. Always. And why? Because hate, true, unapologetic, irrational male hate, is always the default setting. It is the gravity around which women must orbit. So yes, I experimented. I tried skirts, dresses, vintage blouses, bold patterns. I tested the boundaries of the male gaze. And what did I learn? The problem has never been the clothes. It has always been the men, their insecurities, their obsession, their unspoken rules that somehow everyone must obey but them.

𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒲𝒶𝑔𝑒𝓇 𝓌𝒾𝓉𝒽 𝒲𝒾𝑒𝒷𝓀𝑒: 𝑅𝑒𝓉𝓇𝑜 𝒮𝓉𝓎𝓁𝑒 𝒶𝓈 𝒶 𝒮𝑜𝒸𝒾𝒶𝓁 𝐸𝓍𝓅𝑒𝓇𝒾𝓂𝑒𝓃𝓉

It started with a wager with Wiebke: we would dress exclusively in retro fashion—just as society expected. And, naturally, the results were immediate. Men began holding doors, asking politely if we needed help with our bags, suddenly behaving… well, like gentlemen. The same men who objectified us in modern clothes now treated us with respect. A fascinating demonstration of how much clothing can dictate behavior.

But here’s the kicker: while jeans might be comfortable and easy, they did not grant the same freedom. Men who once reduced us to body parts now seemed positively civilized in the presence of natural fabrics, 1950s skirts, and carefully curated ensembles. Beyond the social spectacle, my own health improved: fewer intimate infections, less irritation. Studies suggest that clothing material and fit can directly affect skin and mucosal health. (MDPI: Clothing, Fabric, and Skin Health)

Clothing, Culture, and Confidence

A few months later, I traveled to Israel and wondered how I would be perceived if I kept my hair covered. The reactions were telling: Jewish women treated me as married, with subtle respect; Muslim women viewed me as one of their own, a quiet acknowledgment of belonging. But the real transformation was internal. I felt safer. Stronger. Visible, not just as a body, but as a person. My presence demanded recognition on my terms, not through the prism of male desire. This experiment, this small rebellion of fabric and form, reminded me that clothing is never merely decorative. It is armor, language, and defiance. And when used thoughtfully, it allows women to reclaim space, assert identity, and quietly, irreverently, thumb their noses at a society obsessed with controlling how they look, behave, and exist.

Take the modern debate on headscarves in Europe. On one hand, women are told that covering their hair is oppression; on the other, they are shamed for revealing too much. For over a century, women who respected themselves, who respected their bodies and their agency, have chosen to cover their hair, especially after marriage. And now, in the same breath, laws and social pressures seek to strip them of this choice, insisting that modesty is inherently submission, that visibility equals freedom, and that exposing oneself is the only route to independence. Meanwhile, the underlying paradox remains: men are given free access to the female body—emotionally, socially, and publicly—without responsibility, without accountability. Women are expected to navigate public spaces, dress codes, and moral judgments, while the male gaze dictates the rules. Clothing becomes a battleground where autonomy is tested, where every decision—hair covered or bare, skirt long or short, lipstick red or neutral—is policed. The real rebellion, therefore, is not merely about the choice of fabric or silhouette. It is about reclaiming space, reclaiming agency, and asserting that women’s bodies and identities are not public property. Society may try to legislate, shame, and control—but a woman who understands this principle, who experiments with fabric and form, learns that autonomy is her armor.

As the global discourse intensifies over whether women are oppressed for choosing to wear the hijab, a peculiar phenomenon unfolds in Poland. Here, a group of men donning yellow vests, self-styled as the “Schon-Polizei,” have taken it upon themselves to patrol the streets. Their mission? To photograph women they deem “too revealing” and label them as “whores of Europe.” This self-appointed moral policing raises critical questions about autonomy and the policing of women’s bodies. Ironically, in the same country, women who choose to dress modestly or religiously often face increased harassment. The societal double standard is glaring: women who cover up are subjected to scrutiny and judgment, while those who dress provocatively are often left unchallenged. This paradox underscores a deeper issue within our society — the persistent objectification and control of women’s bodies, regardless of how much skin is shown. This situation reflects a broader trend where women’s choices, particularly concerning their attire, are continuously scrutinised and politicised. Whether it’s the debate over the hijab in Muslim communities or the criticism faced by women in Poland for their clothing choices, the underlying theme remains consistent: women’s bodies are not their own. And here I am, holding on to my childhood dream of wearing dresses like Anne from Green Gables. You know the one – the wide skirts, puffed sleeves, the endless, romantic green fabrics that made every step feel like a storybook adventure. Yet, a question lingers in my mind: am I even allowed to do this? Here’s the twist. I’m over thirty, which technically means I can do whatever I want, right? But paradoxically, I still wonder: what if I wear that dress and some Tomek, Piotrek, Oda, or Karol gives me that penetrating look only men seem capable of, licking their lips while touching themselves at the same time? Weren’t I just planning to walk my dog? Can I feel truly confident wearing what I want?

Because let’s be honest: I am a woman living in a patriarchal country that fancies itself modern. And when my partner tries to encourage me to dress however I like, my brain freezes. “What if he isn’t there when I wear this dress?” I catch myself thinking. How far am I allowed to walk down the street without some man licking his lips at me, reaching, touching, claiming, as if my freedom has an expiration date dictated by his desire?

I am a 33-year-old woman who still dreams of being romantic. Yet, I often call it “just a dream,” because I have learned to be hyper-conscious about what I wear, without judging those who believe they have some bizarre right to critique me. And it’s never enough that men demand my time and attention by sniffing themselves, bending, leering, or behaving in that penetrative way.

What’s more insidious is the judgment from other women. Comments about age, about “too old for that kind of clothing” – they strike deeper than any male glance. Because every woman grows up in a world where attention from men is a battlefield. And any woman who dares to wear what she wants, who dares to feel more feminine than her own insecurities allow, becomes a threat.

So I am judged not only because of my age, or because men expect my attention, or because I dare to choose my attire—but also by other women, who perhaps should know better, yet feel subtly threatened. And here’s the nuance: she doesn’t truly hate you. She’s curious. She worries that your choices highlight what she cannot allow herself. Her attention is training her to protect the man at her side, to prevent him from envying or resenting her, rather than you.

We train girls, from a very young age, to become hyper-conscious, hyper-insecure, to please men, to please society. And when a woman wears something she believes is too feminine, too human, too visible, she becomes the center of the room. She becomes a danger.

So I ask myself: am I strong enough to handle all this attention, as an introvert who naturally recoils from it? Or should some dreams—even if my partner encourages me to wear them—remain in the realm of fantasy? To avoid complicating the delicate balance between men, women, and society?

read more:

Comment below – I want to hear your thoughts.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar